1、亚姆泽·苏基塔什威利,拉蒂·奥奈利,卡卡·金祖拉什威利 主演的电影《开始2020》来自哪个地区?

爱奇艺网友:电影《开始2020》来自于格鲁吉亚,法国地区。

2、《开始2020》是什么时候上映/什么时候开播的?

本片于2020年在格鲁吉亚,法国上映,《开始2020》上映后赢得众多观众的喜爱,网友总评分高达1872分,《开始2020》具体上映细节以及票房可以去百度百科查一查。

3、电影《开始2020》值得观看吗?

《开始2020》总评分1872。月点击量744次,是值得一看的剧情片。

4、《开始2020》都有哪些演员,什么时候上映的?

答:《开始2020》是上映的剧情片,由影星亚姆泽·苏基塔什威利,拉蒂·奥奈利,卡卡·金祖拉什威利主演。由导演迪亚·库伦贝加什维利携幕后团队制作。

5、《开始2020》讲述的是什么故事?

答:剧情片电影《开始2020》是著名演员亚姆泽 代表作,《开始2020》免费完整版2020年在格鲁吉亚,法国隆重上映,希望你能喜欢开始2020电影,开始2020剧情:年轻的耶和华见证会传教士亚娜在一次礼拜中被愤怒的当地人烧毁了她的礼拜场所,她感到十分震惊。她的丈夫大卫设法获得了这次袭击的闭路电视录像。但在他们与年幼的儿子同住的格鲁吉亚偏远村庄里,他对正义的追求引发了一系列事件,他们将发现这个家庭被完全孤立,完全听任敌对的当地警察的摆布

English Title: Beginning

Original Title: Dasatskisi

Year: 2020

Genre: Drama

Country: Georgia, France

Language: Georgian

Director: Dea Kulumbegashvili

Screenwriters: Dea Kulumbegashvili, Rati Oneli

Music: Nicolas Jaar

Cinematography: Arseni Khachaturan

Editor: Matthieu Taponier

Cast:

Ia Sukhitashvili

Rati Oneli

Kakha Kintsurashvili

Saba Gogichaishvili

Rating: 7.3/10

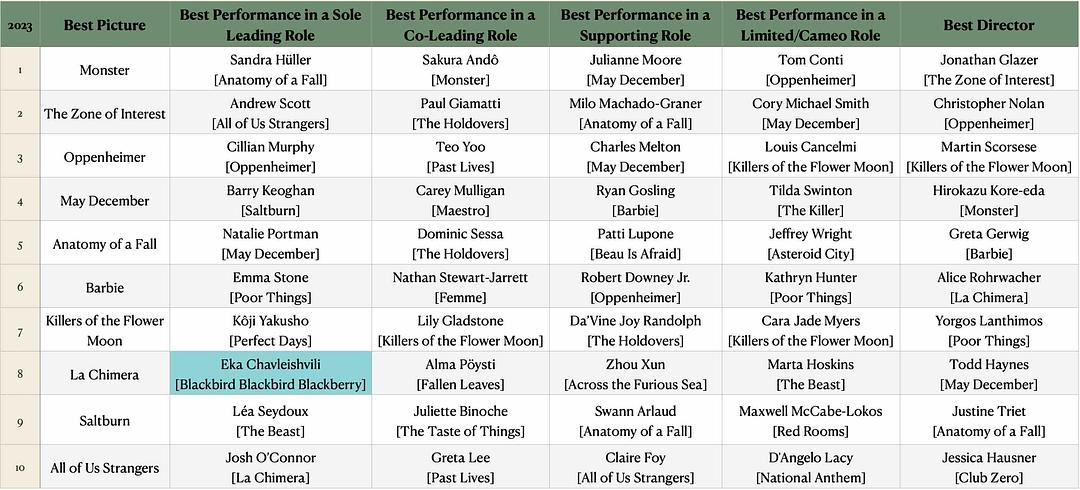

English Title: Blackbird Blackbird Blackberry

Original Title: Shashvi shashvi maq'vali

Year: 2023

Genre: Drama, Romance

Country: Georgia, Switzerland

Language: Georgian

Director: Elene Naveriani

Screenwriters: Elene Naveriani, Nikoloz Mdivani

Based on a novel by Tamta Melashvili

Cinematography: Agnesh Pakozdi

Editor: Aurora Vögeli

Cast:

Eka Chavleishvili

Tamiko Chichinadze

Piqria Niqabadze

Lia Abuladze

Anka Khurtsidze

Tamar Mdinaradze

Ani Mogeladze

Giorgi Kartvelishvili

Rating: 7.4/10

Title: Crossing

Year: 2024

Genre: Drama

Country: Georgia, Turkey, Sweden, Denmark, France

Language: Turkish, Georgian, English

Director/Screenwriter: Levan Akin

Cinematography: Lisabi Fridell

Editors: Levan Akin, Emma Lagrelius

Cast:

Mzia Arabuli

Lucas Kankava

Deniz Dumanli

Nino Karchava

Levan Bochorishvili

Bunyamin Deger

Metin Akdemir

Tako Kurdovanidze

Rating: 7.2/10

Three Georgian films released in the third decade of 21st century, each hinges on an nonconformist female protagonist: a wife of a Jehovah's Witness religious leader whose faith and motherly duty start to crack in the wake of a fate worse than death; a perimenopausal spinster in a rural village belatedly chances upon an emancipating romance which threatens to change her entire mode of life and lastly, a retired teacher, teamed with a purposeless young man, looks for her long-lost niece in an Istanbul area dwelt by transgender people.

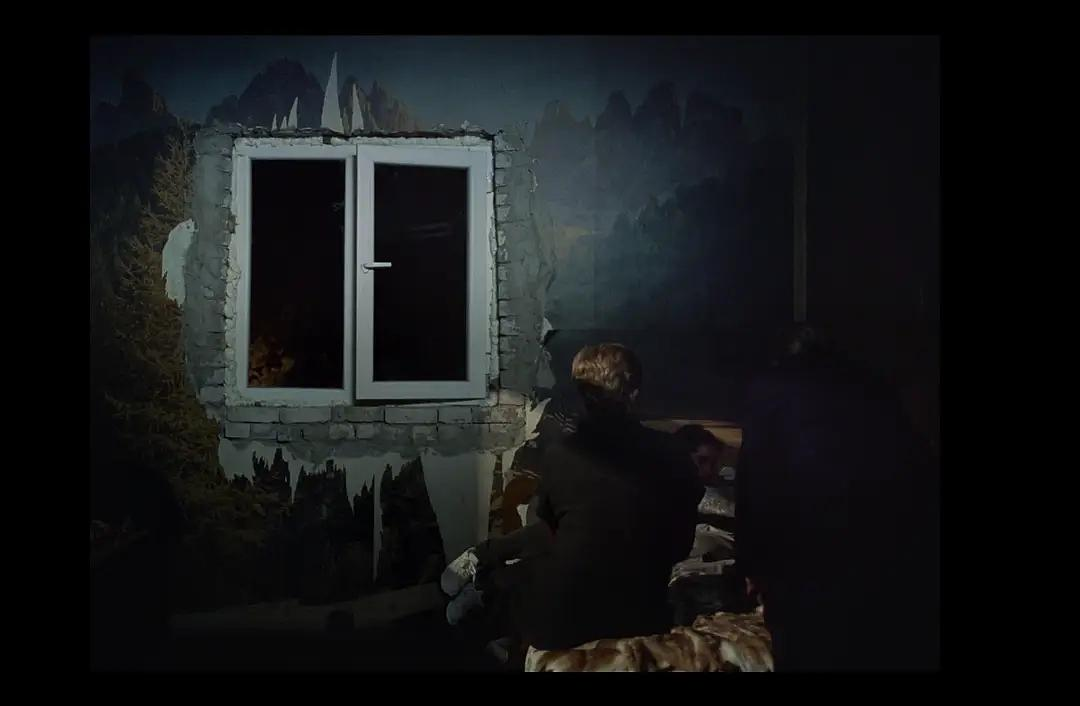

Dea Kulumbegashvili's debut feature BEGINNING is a proponent of slow cinema. Its camera remains static most of the time, from the opening gambit of patiently considering a mass session until it is engulfed in conflagration to the final, VFX-assisted gazing a surreal disintegration of a man's immobile body into nothingness on an arid land. Only for once or twice, Kulumbegashvili's camera stirs, gently, altering its subject. In particular during the sequences where Jana (Sukhitashvili, bringing something enigmatic to her role's docile sufferance), the said wife, is blatantly harassed in her own home by the visiting detective (Kintsurashvili, a dead-pan sadist packaged as a dishy dreamboat, talking about ambivalence and the danger of facile temptation...). Jana's compliance under duress is underlined by the unexpected change of the camera's angle, from her to the detective sitting on the coach and bossing her around, asking increasingly private questions about her sex life with her husband David (Oneli, also the co-screenwriter). Such change serves as a cue to sharpen a viewer's attention, which is mindful to be supplanted by stultification on account of the camera's relentless, self-designated passivity.

Jana's own passivity is exacerbated by a vesperal, alfresco ravishment at the hands of the detective, mercifully shot in a long shot, integrated with the uncanny natural environs. After the fact, Jana visits her mother, who, unwitting of what has happened, advises her not to come clean to David, which betokens the older generation's dyed-in-the-wool turning-the-other-cheek submission in order to sustain a peaceful appearance in a marriage (told through an aggravating anecdote masked as a cherished childhood memory). But by a strange quirk of fate (lacunae are part of the furniture in the film's ellipitcal narrative), David will get wind of Yana's misfortune. However, his reactions and consequentially, actions only occasions Jana's existential disillusion, not just to David, but also to a larger patriarchal egotism and cruelty, and to their religion. In the event, Jana refashions the choice of filicide faced by Abraham (echoing David's sermon in the beginning), as a radical and profound protestation of her inarticulate misery.

The camera's unwillingness to budge as an artistic choice often cuts both ways. On one hand, it facilitates precision in compositions and settings (a chink of light can be foreshadowed as a sword bisecting a child's body, for instance), strictly curtails what audience is permitted to see, and assumes an ostensibly objectified stance as if we are watching footage from a CCTV camera (albeit a highly styled one). On the other hand, such a modus operandi can be pretty wearing for audience and betray the filmmaker's authoritarian pretension, especially when every blocking, every gesture, even every breath of the actors tend to be consciously perceived as the outcome of a deliberate calculation. A film loses its spontaneity and thus, it has no vigor but a propensity of being unbearably didactic (Dietrich Brüggemann's 2014 film STATIONS OF THE CROSS is an anathema in this case). Thankfully, BEGINNING is shored up by Kulumbegashvili's peculiarly engaging observance of the mindscape of a woman's "beginning" towards rebellion and radicalism. It is a rude awakening for the world to reassess the whole system of the powers that be in our social, political and religious spheres where malaise and acedia is hard to dissipate.

BLACKBIRD BLACKBIRD BLACKBERRY is Elene Naveriani's third feature, nimbly shot in a rich and vibrant palette. Etero (Chavleishvili) is 48, single, runs a small store by herself after the death of both her father and brother in a jerkwater village. Her life in a rut is gingered up by her carnal knowledge with Murman (Chichinadze), a married teamster routinely proffers the goods for her store. Surprisingly, it is Etero who takes the plunge as the instigator to ignite their passion, with the intention to bid farewell to her awkward virginity.

In its opening passage, while picking blackberries, Etero almost falls off a ravine after being amazed by the sight of a rare blackbird. Later she imagines her own drowning, which signals a latent urge to bring herself out of her status quo. So after losing her virginity, Etero is slowly taken by her courteous paramour. They exchange texts on their phones. Etero loosens up and tells him about her past and the causation of her spinsterhood (another victim of patriarchal repression and passive aggression, she is blamed by her father for her mother’s death by giving birth to her, but why oh why, a child shall never be reproached in such a tragedy, how could a fetus know?). The two carefully arrange their assignations out of the reach of the local scuttlebutt. Naveriani's film is a tender-hearted portraiture of a lonesome woman's inchoate feeling of loving and being loved, without any hidden agenda, except some contretemps.

When their affair turns more serious, as Murman finally proposes to start a new life together with her in Turkey, and that becomes the deal breaker. Etero might take a fancy of changing her monotonous existence, yet it shall never encroach on her independence. She has fully envisaged her future after retirement, settling down with and taking care of another man in a new country isn't it, on which Etero really puts her foot down. That said, BLACKBIRD BLACKBIRD BLACKBERRY unavoidably plays a cruel joke on her in the end. Audience has no sooner suspected the patter of tiny feet than Etero dreads that something far more malignant might be growing inside her body. The final shot is a close-up fixed on Etero's face mixed with tears and laughter. An ambiguity suggests relocating to Istanbul with Murman might be the best option for her now. But what is anything but ambiguous is the overtone that for a woman, only her maternal responsibility could possibly overrule her innate yearning for independence. It is a sacrifice many a member of the fairer sex chooses to commit and Naveriani's film is level-headed enough to broach it but consciously leaves Etero's decision moot.

Chavleishvili, with her owlish eyes, dark eyebrows, frizzy curls and phocine figure, makes for an unconventional cynosure. At first glance, her Etero is kooky, even spookily assertive in her sexual maneuver, a type one might intuitively give a wide berth to. But in time, her softer side will emerge out of her carapace. Etero is understanding, compassionate and self-sufficient, not mincing words when being belittled, meanwhile she is also smart enough to insinuate her way back into the small circle of the local women after being ghettoized for her blunt remarks. When ensconced in the romance with Murman, she is well transitioned to be more reticent, receptive and tractable. It is not an exaggeration to proclaim that the film is preponderantly anchored in Chavleishvili's miraculously versatile ability to fully embody and balance Etero's ordinariness and idiosyncrasies.

CROSSING is Levan Akin's follow-up to AND THEN WE DANCED (2019), his queer-affirmative breakthrough. Here, queerness is again erected in the epicenter. Lia (Arabuli), a Georgian retired history teacher, is hell-bent on tracking down her transexual niece Tekla in Istanbul, and reluctantly allows Achi (Kankava), a young man escaping from the toxic family of his married elder brother, to tag along when he purports to know Tekla’s address.

Following the death of Tekla's mother, Lia is propelled by her monomania of fulfilling her sister's dying wish. But it is also her chance to reunite with her last kin, and offers an overdue apology for her generation's collective failure to support and protect their trans-offspring. Lia also forges a bumpy relation with Achi, who is determined to secure a job in the big city despite that he is wanting in Turkish. For Lia, the language barrier is much bigger. Even on the sideline, she can twig the insalubrious situation of the trans community. Yet, CROSSING doesn't dwell on its underside, instead sees it with rose-colored glasses, especially when the world as we know it is getting more and more belligerent, hostile and divisive, which has come to be a new trend of the queer cinema.

Paralleling Lia's border-crossing quest, a subplot revolving around Evrim (Dumanli, a graceful dame magnetically vaunts her otherness like nobody’s business), a trans-woman and a self-made lawyer who indefatigably offers succor to the marginalized and the downtrodden, is deceptively lead audience to believe she might actually be Tekla. So we are safe in the knowledge that their paths will eventually cross and an emotional reunion is down the road to warm the cockles of our hearts.

Emotional yes, and the two paths do cross, but a reunion doesn't materialize. Evrim is kind and helpful but Tekla's whereabouts turn out to be a needle in a haystack. Akin even fantasticates a fortuitous encounter to let Lia get her pent-up regret and remorse off her chest, which in turn, heartens her to continue her mission in the coda, hope springs eternal!

A tough-as-nail Arabuli stupendously conducts a commanding presence as Lia. Her schoolmarmish, stolid comportment cannot conceal her maternal consideration (despite herself, in time she will morph into a mother figure to the hapless Achi), a nostalgia of her youth (when she finally hangs loose under the influence, she scares off a hospitable compatriot and laments over her long-lost pulchritude) and a grievance over the opportunities she has missed out in her life (on which the film never expounds), for too long.

More appositely regarded as an apologue about generational guilt and repentance than a preconception-bucking curio about trans-community, CROSSING might wear its gender-neutral heart on its sleeve, but in the end of the day, it appears that it is youngsters like Achi and street urchins who are needier than the doughty, resilient transpersons.

Heralded by the triptych, centering on complex, uncharacteristic female characters and underscored by unique voices from women and genderqueer directors, a new dawn of Georgian cinema is definitely on the horizon. These films can be relished like a refreshing, invigorating, even rejuvenating nectar from a wondrous fruit that is endemic to Georgia's own fertile soils of creativity and courage, including the reassessment of its troubled history and the new-found confidence of marching into a more civilized future. Paraphrasing Isabelle Huppert’s recent proclamation in Venice, where Kulumbegashvili's sophomore film APRIL (2024) is honored with the Special Jury Prize, “I have good news for you, cinema is in a good place!”.

referential entries: Levan Akin's AND THEN WE DANCED (2019, 7.6/10); Dietrich Brüggemann's STATIONS OF THE CROSS (2014, 4.2/10); Luke Gilford’s NATIONAL ANTHEM (2023, 7.3/10).

《开始》,俄罗斯女导演迪亚·库伦贝加什维利的处女作,曾入选戛纳2020官方片单并获得圣塞最佳影片导演剧本三项大奖。

影片背景设定在格鲁吉亚,主角是年轻的耶和华见证会传教士亚娜。亚娜原本是一名女演员,但因与耶和华见证会传教士大卫结婚而放弃工作,在教会帮助丈夫。亚娜和丈夫所信仰的耶和华见证会本就是基督新教边缘教派之一,而在主要信奉东正教的格鲁吉亚,更是异端般的存在。故事便开始于这一矛盾。

(以下文字包含大量剧透)

被压迫的女性

影片开场是大卫和亚娜在教堂讲述亚伯拉罕献祭儿子以撒的故事,但一群歹徒用一场纵火烧毁了大卫和亚娜的教堂。

在袭击之后,丈夫大卫踏上寻求重建教堂之路,而独自在家的亚娜则遭到警探亚里克斯的盘问。

简单几个问题之后,亚里克斯竟询问起亚娜和丈夫的性生活。亚娜一开始迟疑不回答,在亚里克斯的威胁与逼迫下,她勉强回答是或不是,接着亚里克斯让亚娜坐到自己的身边,让她的手摸自己的下体。

其后一天晚上亚里克斯在溪边强奸了亚娜。这是一个固定长镜头,小溪的流水声盖过了人声,人物只占画面的一小部分,但这个镜头却给人十足的震撼。画面中的亚娜渺小而无助,任由亚里克斯殴打,在强奸完成后,亚里克斯把泥巴糊在亚娜脸上并举起石头想要杀死亚娜。

在这个长镜头里,导演流露出女性视角下独有的温柔力量,和很多男导演不同,这里的强暴戏的重点并不在于单纯展示暴力,而是聚焦暴力下的女性境况,给予她们最基本的关怀与尊严。

被侵犯后的亚娜在洗手间里脱下衣服,缓慢地清理身上的泥水,一道道鲜红的血痕开始显露出来。之后不安的亚娜只得到母亲家里借宿,母亲和妹妹的存在一定程度上安抚了亚娜,但这并不能抚平她的伤痕,尤其是当母亲讲到小时候的亚娜晚上哭闹,而喝醉的父亲将她们母女赶了出去,母亲只得抱着小亚娜在雪地里挨过一晚。

影片全程采用4:3的方向画幅,逼仄的取景框给观众强烈的窒息感,通过这样的镜头,导演全方位冷静客观地展现了保守的宗教生活与严苛的男权社会以及糟糕的家庭环境对女性的压迫与摧残。

寻求重建教堂的丈夫回家了,却意外发现了警探亚里克斯盘问亚娜的录音,尽管亚娜告诉他亚里克斯强奸了自己,但丈夫的第一反应不是安慰而是怪罪她:万一这事被教会的长老知道了怎么办?亚娜哭着让丈夫惩罚她,男人犯的罪却让女人来赎,另一场悲剧才刚刚开始。

赎罪与献祭

严苛的宗教生活下,亚娜自觉有罪与不洁,被骚扰、被强暴、被误解全都成了她的错,而这一切都始于警探盘问的那一晚。在警探问亚娜是否喜欢给老公口交时,亚娜不仅回答是还接着说了一句老公也很喜欢,接着在摸完警探的下体之后她反而如释重负。导演在这里的暧昧处理,并不是表明亚娜想要和警探发生性关系,而是她在长期严苛的宗教生活里备受压抑,警探的这一生理刺激反而给了她的欲望一个出口,然而恰恰是这一举动让亚娜以为自己有罪,成为她后面想要赎罪的根源。

此时的影片已进入尾声,在给儿子洗完澡后,丈夫问亚娜为何儿子这么早就睡了,亚娜回答道:“我杀了他!”

如何理解亚娜杀子这一举动?我的看法是赎罪。

在影片开头亚伯拉罕献以撒的故事里,天使对亚伯拉罕说你是害怕上帝才会献祭,亚娜也是如此,在被宗教压迫异化,出于对上帝惩罚下地狱的恐惧,觉得自己是罪人,她只能学习亚伯拉罕献祭儿子,以寻求赎罪。

亚娜完成了赎罪与献祭,而这恰恰是建立在对女性的压迫与对人性的异化基础之上,是一出彻头彻尾的悲剧。

至此,开头与结尾完成了一个完美的闭环,开始即是结尾。

真正的洗礼

在基督教中,有一种洗礼方式是信徒平躺着浸入水中,这一仪式被称为浸礼。影片中有两个和浸礼非常类似的桥段,一是影片中段亚娜躺在树林里,二是结尾处警探亚里克斯躺在干涸的土地上。

亚娜躺在树林里发生在警探盘问后,亚娜压抑的欲望有了出口后,她重新获得了个体的生命力,她静静地躺在树林里,耳边是虫鸣声鸟叫声树叶的婆娑声,这一刻没有宗教,没有男人,只有自己的存在,她真正地获得了幸福与平静。

影片结尾处,犯罪的警探亚里克斯在逃亡的路上来到一片干涸的土地前,慢慢地躺下,身上渐渐长出泥土,最后成了一尊泥塑,被风中吹成了散沙。

这两段艺术化的处理,有的人说是赞美女人的生命力,谴责男人的罪行;也有人说亚娜和亚里克斯是一对偷情者,这一呼应是对男权社会的反叛和对宗教信仰的质疑。

两种解释都有值得探讨的地方,而这也是本片的优点,与高超形式所匹配的丰富且具有可解读性的内容,不愧为2020最强的处女作之一。

当Yana的丈夫David在礼拜堂组织活动时,礼拜堂遭到了极端主义的恐怖袭击。在恐怖袭击之后的晚上,David告诉Yana说为了事业,他需要重建礼拜堂。Yana支持他,但是Yana不想陪他去见教会领导,她想独处。由此也引发Yana内心的倾诉,她说她好像在等待什么东西开始或者结束,或者人生这样流逝,但她好像不在这里。David给Yana提供了一个解决方案,她需要找一个工作。

在David离开之后,一个警察(Alex)上门问询,他进门后对案件只有只言片语的问题,然后他开始攻入Yana的私生活。他问Yana说她老公会在沙发上操(f**k)她吗?这个问题与案件不仅无关,同时它攻入到Yana生活非常私密的部分,而且问法极具侵略性。Yana一开始迟疑抗拒不回答,在威逼利诱下,她开始回答Alex的问题。开始Yana回答是或者否,最多仅回答问题本身问到的部分,不提供其他信息。到这里,Yana一直在抵抗。但是从Alex问到Yana喜欢给她老公口交吗时,Yana除了回答她喜欢之外她还提供了一个额外的信息,就是她老公也喜欢。Alex对此表示赞赏,这也意味着Yana的抵抗开始松懈,因为她不仅仅是在被动回答问题,而是她也在参与这个过程。但是这个参与并不意味着Yana主观想和Alex亲近乃至发生性关系,而是她开始放松自我主体对外界入侵的警惕性和防御性。警惕性和防御性对于人身体上和心理上起保护作用,它们保证着人可以做好准备,不让外界的危险轻易造成自己丧失对生活的控制。但是Yana开始放松这个部分。

一段时间后,门铃响起,Yana出门去寻找。门铃响起是一个讯号,说明外面有人来,但是在半夜不知道外面来的人是谁的情况下,外来者可能是有危险的,但是Yana还是跑了出去。这与之前Alex入侵不同的地方在于,上一次Alex是攻入Yana的房子,而这一次是Yana跑出本可以保护她的房子。这说明Yana在寻找,她在下意识靠近那些危险。寻找是一个动作,背后的目的是要找到她想要的东西。那Yana想要的是什么?

Yana的老公作为宗教的领袖,他所在的礼拜堂遭到极端分子(邪教) 的攻击,以这个攻击为起点,Yana的内心平衡被打破,她心里有个部分被触发,但是她又无法去满足那个部分,所以她出现了很多抑郁的行为,例如她站在树下发呆,卧室里与丈夫的争论等等。影片里多次提到天堂与地狱,Yana老公作为领袖,他所代表的就是天堂,Yana同他在一起,其实指代了Yana靠近天堂,邪教的攻击代表地狱,地狱搅乱了原本看似祥和的生活。Alex是警察,警察是道德力量在人间的代表,它是正义的,同时Alex入侵Yana家里以及强奸Yana,这是道德败坏,是魔鬼。天堂与地狱,或者上帝与魔鬼,是Yana存在的两个极端。

Yana与老公在卧室争执时,她多次提到她想一个人呆着。影片中间有一段长达几分钟的Yana躺在地上闭着眼睛一动不动,一度只有鸟叫和零星的几个虫子爬来爬去的画面。这与Yana跟老公相处形成明显的对比。当她一个人躺在地上时,她感到安静满足。之后Yana的妈妈讲到Yana小时候她抱着Yana在外面的时候,Yana很快就安静地入睡了。这也跟Yana在卧室里跟老公的诉求一样,她想要自己独处。独处是一个方式,这个方式保证了她可以暂时离开老公,离开孩子,甚至在她婴儿时期离开醉酒的父亲。独处的诉求之下是Yana作为一个个体,她自己想要什么,这与她的老公,儿子,父亲都是无关的。而且独处保证了她可以离开老公,这个宗教道德领袖,做回人类。但是当她向老公倾诉时,老公说你能像一个正常人一样说你想要什么吗?Yana其实已经在表达她想要什么,但是这在老公看来是不正常的。换言之,如果Yana要像一个正常人,她就无法表达她想要什么,反言之,如果她想要什么,她就不是正常的。老公所代表的天堂或者上帝,表示Yana只能顺从。但是在无法违背上帝的情况下,又想做不能被上帝允许的事情时,这就有了魔鬼。魔鬼是上帝的对立面,他代表着堕落与惩罚。这与Alex的出现一样,他代表着Yana想要违背上帝就得接受的惩罚。堕落是Yana自己想要什么或者像个人类一样这一诉求在上帝看来的定义,放弃防御和寻找是她向魔鬼靠拢,而被强暴就是这些诉求招致的惩罚。

卧室的争吵里,Yana说她好像不在这里,这是因为她自己身为个体的感受与欲望被压抑,当这些欲望不能被释放与满足时,她是无法感受到自己的存在感的。她说她在等待一个开始或者结束。开始与结束都表示着自己个体的愿望被释放出来,开始预示着当这个欲望释放出来后,她可以开始新的生活,这是她身为人的本能,人本能希望自己的欲望被满足,这样才有活着的感觉。结束意味着欲望一旦释放出来,她的生活就完了,这是因为这些欲望与想法,都会招来魔鬼惩罚,毁灭她。

天堂与地狱的两极之间,还有人间,上帝与魔鬼之间,还有人类。Yana的诉求,无论是独处,还是想追求自己想要的,这都是身为一个世间之人再正常不过的需要。所有这些需要本可以正常表达,生根发芽,开花结果,但是,对于特定社会形态下的女性,追求个体的意义与价值就等同于对主流道德的背叛,而这个背叛的结果就是因为道德沦丧而招致的唾弃,惩罚与毁灭。

上午在日记刚发了最喜爱的电影,晚上就拿了四项大奖,把日记内容转载过来,并增加导演访谈细节。

“这部电影目前在全部主竞赛片单中喜爱度排第一,在看片的前一天得知该片已经在多伦多影展斩获费比西大奖,所以又多了一分期待。果然在观片时内心受到了极大的触动,可以说这依然是一部中产阶级焦虑的类型,也是我最爱的类型。

本片背景设置在格鲁吉亚一个安静的小镇,开篇就展示了一个宗教社区遭到极端主义团体袭击的场面。在此之后,社区领袖的妻子由于此事件遭受了一系列超乎想象的打击,甚至连她基本的日常生活都被彻底毁灭。

本片再次验证看似安逸的中产阶级在遇到和国家机器,社会体制发生冲突时的脆弱,但是与底层的脆弱有所区别的是,中产阶级安全感的土崩瓦解是逐步的而不是瞬时的。如果乖乖顺从,当然相安无事,怕的就是遇到想要追求公平正义的片中这家人,如何被当作到温水中的青蛙,直到水沸的那一刻。

在略微剧透的情况下分析一个情节的隐喻,对于不喜剧透的朋友表达抱歉,因为对此有太强的表达欲。这是在河岸中关于强奸的一个长镜头,此时我又想拿大家最熟悉的《不可撤销》的同样片段做对比,近距离直视全程,暴力血腥再加上女主的惨叫令观众在试听层面达到非比寻常的震撼效果。

本片类似情节的设置完全没采用这种方式,而是以一处河岸的广角远景视图,背景声音充斥着潺潺的溪水声,人物只占据画幅的1/5,导演在访谈时提到该画面如此设置是因为近景展示针对女性的暴力太可怕了,会让观众联系到自身,感受极度不适,所以用远景并遮盖声音处理,抽身在外去观看可以更加客观去冷眼直视。

确实在这种视角下我看到了一些深层次的体会,女性被强奸的过程就很像是体制对个体的碾压;过程中还被自己的衣服蒙住头,这是指即使被碾压却还无法认清对方的真实面貌;接着强奸过后还被满脸涂满河中泥沙,代表碾压完也要闭嘴,不要乱说话;与此同时强奸者还举起了石块,随时置对方于死地,暗示如果你敢表现出丝毫反抗,立即毫不留情让你死无全尸。

出生于俄罗斯在格鲁吉亚长大的女导演迪亚·库伦贝加什维利曾在纽约学习媒体研究,并在哥伦比亚大学艺术学院电影系任导演。她表示不止在格鲁吉亚,不管在哪个国家都会发生这样的故事。”

导演访谈:

问题 1:您为何把宗教元素贯穿电影的全篇?

我和卡拉斯(不认识这个人是谁,不知道翻译是否准确)聊过,宗教是一个很难的话题,这不是个人选择,我感兴趣的是这种选择会让人们知道该如何去做,其实为了研究人们如何在这种宗教体系下生存,我们做了很多研究工作。

问题2:这个电影里面的自然元素非常惊艳,如何决定选择这里?

对于自然风景的选择,是因为我在山间长大,当我还是小孩,感觉并没有很强烈。但是在我长大后感觉变得倍加强烈。对于片中的暴力元素也是如此,需要近距离去观察,生活也会改变所发生的事件。

问题3:您这部电影用多久完成的?

我们用45天完成整部作品。

问题4:如何选择的女主?

我们探讨了很久女主的角色,很高兴可以选中她,我们观察了她的日常生活,她做什么其实很重要,很难找到一个人饰演这样的角色,挑战比较大。

问题5:请男主回答一下和女主演出的配合度?

男主:我很惊喜知道自己可以饰演这部电影,离开拍的时间并不长,然后女主教会了我很多东西,减少了我的拍摄的压力,很感谢她。

问题6:这部电影拍摄于格鲁吉亚,以后打算继续拍这里的电影吗?

格鲁吉亚具有很长的历史,每个人来了都有不同的感受,我在电影中运用了很多技术,我也希望可以在这里拍更多不同类型的电影。

问题7:在影片中您可以很安静的运用大自然,如何做到的?

导演:对美的寻求,不都是独特的,而是复合的美,创造出安静的氛围,可以更大程度的倾听演员,比如片中的脚步声很重要,观众可以通过这个声音找寻他们所听到的声音。

问题8:能不能谈一下女主所经历的强奸与女性的独立

导演:两年来,我做了很多针对女性性暴力的研究,这个话题很难深入,我之所以选择用远景是因为这个场面太可怕了,会让观众联系到自身,所以能够理解其他人的痛苦很重要,在其中那段母女对话中也没透露强奸的事,或许因为妈妈并不想知道女儿遭受的痛苦,这属于没有回旋余地的电影,我们该如何做去阻止伤害有更重要的意义。

要不是去年戛纳因疫情取消的话,这部《开始》估计能引起更广泛的热议。这位出生于俄罗斯、成长于格鲁吉亚的女导演迪亚·库伦贝加什维利瞄准格鲁吉亚女性在社会中遭受的多重压迫,并以冷漠的画面展示女性遭遇暴力性侵犯,其令人震惊的程度直逼当年戛纳首映的《不可撤销》。nn故事讲述年轻的耶和华见证会传教士亚娜在一次礼拜中被当地人烧毁了她的礼拜场所。她的丈夫大卫设法获得了袭击的闭路电视录像。但在这个格鲁吉亚偏远村庄里,他对正义的追求引发了一系列无法挽回的悲剧事件……

风格带有北欧影片的疏离冷漠感,开场第一个镜头就让我误以为是在看瑞典导演罗伊·安德森或金棕榈导演鲁本·奥斯特伦德的作品。固定机位长镜头的摄影构图构成了整部作品的叙事基调,平均每个镜头的时间为4至5分钟,有的更接近10分钟(比如开头纵火和中段强奸),这使影片节奏相当缓慢迟缓。nn原来,影片的监制是墨西哥导演卡洛斯·雷加达斯(这位也曾是戛纳嫡系成员),这似乎能解释库伦贝加什维利在长镜头里开拓画外空间的尝试。女主角在家中被警察逼问的一段,以及丈夫质问女主角的一幕,观众可听到镜头外人物的台词,感受到没进入画面人物的强烈情绪。导演透过这种手法制造剧情张力,拓展观众的想象空间。如此极端的美学风格带出不太平衡的感受,有些场景相当惊艳(比如女主角躺在草丛中感受大自然的画面),有的则过于僵硬,甚至有故弄玄虚的嫌疑,令影片显得过于冗赘。

然而,相比起风格上的稚嫩和失准,这位女导演最出色的是主题的呈现。从一开始挑明这个地区不同宗教的矛盾对抗,之后由警察角色引出制度的黑暗腐败,最后再转到男权对女性身心的压迫和控制,递进式地展现出女性在社会所承受的各种歧视和侮辱。女主角在遭遇警察性侵犯后,从她身边亲人——母亲的态度和丈夫出人意表的反应,都印证了女性在这个传统社会里难以摆脱的悲惨命运。